What it means to learn to read

Let's start with explaining what it means to learn to read. It means learning to translate the graphical (letter) form of a word into its sound. However, this alone is not enough. It is also necessary to understand the meaning of what is read. Thus, reading involves two aspects: phonetic (sound) and semantic (meaning).

Throughout human history, there have been many different approaches to teaching reading. These methods have evolved, helping learners acquire this skill more quickly and comfortably.

I would like to introduce you to my reading instruction methodology and explain how it was developed and why it is effective.

In short, I was influenced by modern British methods for teaching both adults and children, observations of my students during lessons, analysis of these observations, and an understanding of the achievements in developmental psychology. The methodology incorporates teaching materials from British specialists, along with exercises and games that I have created. It is suitable for children aged 6 and up, with some elements adaptable for younger children. This approach can also be applied in a condensed and accelerated form for teaching adults to read.

The methodology consists of several stages, each addressing a key task in the process of acquiring reading skills.

Stage One: Pre-Reading

In the pre-reading stage, the child associates the visual image of an object with the sound of that same object.

At this initial stage, I use flashcards with pictures and words. For example, like these (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Usborn. Everyday words Flashcards

Here's how the flashcard activity generally works: the child looks at a card with a picture and repeats the word after me that corresponds to the object in the picture (see Figure 1). I then show the cards one by one. After a certain number of "shows" and repetitions, I display the familiar cards again and ask the child to read the words themselves, which they usually manage quite well.

However, if I ask the child to read the same words on the reverse side of the cards, where the picture is absent (see Figure 2), they are likely to struggle.

Figure 2. Reverse side of picture flashcards. Usborn. Everyday words Flashcards

I reached this conclusion based on my observations of my young students. Later, I found an explanation for this. According to research in developmental psychology, a child memorizes the visual image of an object and the associated sound of the word that designates that object. Essentially, the child isn't actually reading! For them, the main focus is the picture, in which they recognize a familiar object—an apple, a book, a pencil. At this early stage of learning, language acquisition largely occurs at the oral level.

You might have noticed how children, while flipping through a book, tell a story or fairy tale as if they are reading it. In reality, they are simply retelling a narrative they have previously heard and remembered.

Stage Two: Learning to Differentiate English and Russian Letters

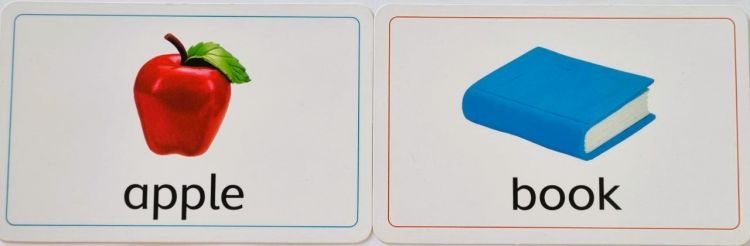

The task for the second stage is to learn to distinguish between English and Russian letters.

Figure 3. Letters of the English Alphabet

In practice, with younger students, we usually cover the first and second stages of learning to read simultaneously. It's important to learn the sequence of letters and to distinguish them. This means not only differentiating between the letters of the English alphabet but also not confusing English and Russian letters that look similar.

For example, uppercase letters like the English B and the Russian В ("V"/Вэ), or the Russian Н ("En"/Эн) and the English H, and lowercase letters like the English n and the Russian п ("pe"/пэ). Without this distinction, a child might read the word "Hat" as "Нэт," which highlights the importance of this stage.

To help children distinguish between letters, I've developed a variety of activities, the main one being Spelling Dictation or Letter Dictation. This is the primary tool for practicing letter distinctions. In this activity, the teacher dictates only letters, not whole words. During the task, the student sees how letters form familiar or unfamiliar words. At the end of the activity, the teacher checks whether all the letters have been correctly written. The exercise is also done in reverse: the student selects words and dictates them letter by letter to the teacher, who is then "tested." The idea is to create intrigue for the student and encourage them to recall and name the letters.

At this stage, it's also important to learn how to write these very letters correctly. In the modern world, people primarily write with printed English letters, but whenever possible, I recommend mastering cursive handwriting to increase writing speed. Handwriting worksheets can be found in some modern resources, aiding in this skill acquisition.

Stage Three: Emotional Familiarization with English Words

The task at this stage is to emotionally familiarize oneself with English words. I propose memorizing simple stories or rhymes containing very basic, short words and phrases. For example:

"A fat cat sat on a mat

And ate a fat rat."

These stories or rhymes help children associate words with emotions and imagery, making the learning process more engaging and memorable.

At this stage, I enhance the rhyme by adding several short words containing the same vowel sound, such as "a bat, a cap, a van, black," and others. Then, I create simple word combinations for reading practice, like "a black cat, a fat rat, a grey bat, a red apple," and so on.

During this stage, students become accustomed to English words and gain some experience in understanding how words are structured and how letters correspond to sounds. This builds confidence in acquiring the skill of reading.

Stage Four: Transition from Pre-Reading to Full Reading

Let's revisit the first stage with flashcards. As I mentioned earlier, if I ask a young student to read a familiar word written on a card without the accompanying picture, they're likely to struggle.

Figure 4. Reverse side of picture flashcards. (Usborne. Everyday Words Flashcards)

It's evident that our goal is to transition from "pre-reading" of picture-word associations to full reading of words. Firstly, it's important to note that English has a very complex orthography, with many exceptions to pronunciation rules. There's a saying about English: "Spelled Liverpool, read Manchester." For instance, most vowels or vowel combinations have multiple pronunciations, and some letters or combinations are not pronounced at all when reading. How then can one learn to read "properly," that is, to translate the graphical form of a word into its sound?

Method 1: "Phonics"

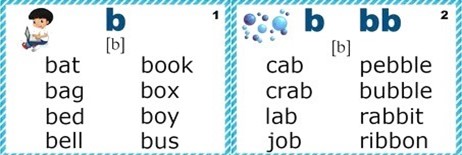

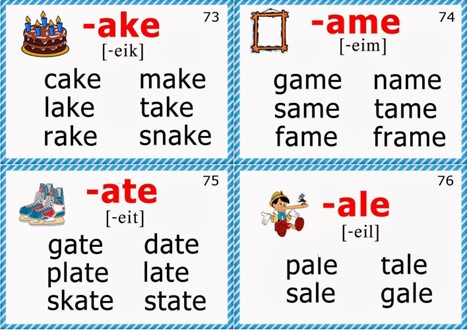

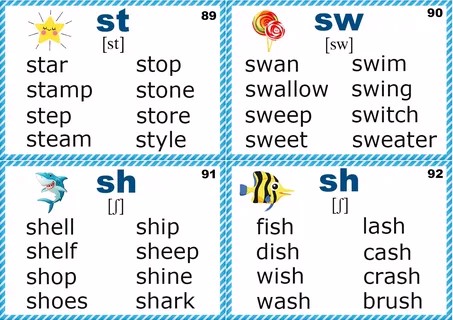

"Phonics" is a British methodology aimed at mastering the correspondences between letters and their sounds, as well as letter combinations and their pronunciation. Phonics materials typically consist of cards featuring small groups of words with common letters or letter combinations. Working with these cards helps children gradually memorize various sound-letter correspondences. See Figure 5 for an example of what phonics materials might look like.

Figure 5 and 6. Phonics

In essence, phonics is about teaching students simplified reading rules. Words are grouped into logical phonetic categories, spelling has a vivid visual form, and students simply repeat words with the teacher multiple times. No one asks the student to memorize correspondences deliberately. Phonics can be used to teach adults as well.

Method 2: Learning Words by Themes

While phonics presents a variety of words with similar sounds, this method introduces students to word collections based on themes.

For instance, "Objects" includes a list of everyday items found in school and at home, "Food" introduces vocabulary related to food items, "Colors" covers different hues, and so on. By the way, instead of using dictionaries, which many of us used to keep in school, college, or just for personal reference, I prefer using word block lists in notebooks. The advantage of this method is that learning words by themes is more emotionally engaging and relevant to the child's life. In phonics, we encounter words from various spheres of life and even from different grammatical categories, such as "what, whale, whip." (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7: Phonics.

It turns out that the more words a child knows and can read correctly, the less need there is to learn reading rules. Build up a passive vocabulary, and the reading rules will be memorized naturally!

In general, my practice shows that the best solution is a combination of these two approaches. Phonics work on absorbing typical combinations and pronunciation variants, while learning words by themes helps apply reading rules without memorizing them.

Stage Five: Mastering Transcription

In modern schools, as early as 2nd or 3rd grade, students are required to memorize not only letter combinations but also transcription symbols. This further increases the complexity of the student's tasks. They need to remember not only how a particular combination of letters sounds but also master the symbols that encode various English sounds. It's challenging! However, if symbols are learned gradually, in portions, allowing time for the assimilation of this complex material, it's achievable. Some of my students, as early as 2nd grade, can write individual words using transcription symbols.

To teach transcription, I use cards from the "Britannia" publishing house from 2009. (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7: Transcription study cards. Each type of sound has its own color.

Stage Six: Understanding the Meaning of What is Read

As mentioned earlier, reading has two aspects: phonetic and semantic. So far, I've discussed how to master the phonetic aspect or reading technique, i.e., learning to translate the graphical form of a word into its sound. What comes next? We need to learn to understand the meaning of what is read. This applies to individual words, sentences, and texts.

Having mastered the reading technique, a student may correctly read a new, previously unknown word but not know its meaning. Alternatively, they may read a text with excellent pronunciation but struggle to provide an adequate translation. While the meaning of individual words can be found in dictionaries, understanding the meaning of sentences and texts requires understanding sentence structures, considering context, and other factors. The semantic aspect of reading will be the subject of another article.

In conclusion

I'll answer a question that parents often ask: How long will it take for a child to learn to read in English? To complete all the necessary stages of the program, it will take approximately 10-15 lessons. However, the speed of progress through each stage will depend on the child's language learning abilities and the frequency of lessons. For example, one student began reading short words as early as the first lesson, while another needed 5-7 sessions to master the alphabet and only a small selection of short words. In any case, it's crucial to support the student at every stage of learning, praising even the smallest achievements. This boosts their confidence and motivation to learn, ultimately enhancing effectiveness! I wish you enjoyable learning as you embark on reading in English!

Before starting the course, we offer a 20-minute trial lesson where you can meet the teacher, choose the right course, and outline your learning plan.